Some people think the act of government spending a dollar creates value. As if the dollar was not circulated from somewhere prior to ending up in a government account. The idea of a circulatory system for money leads to the metaphor of spending “pressure” drawn from the measure of blood pressure in our circulatory system. Government taking away taxes or going into debt creates pressure on taxpayers to pay it. Simple, right?

And yet a simple evasion is routinely offered—a kind of “economic transubstantiation”[1] where government spending consecrates a new value out of nothing, costing nothing and only giving life to an economy.

However, to the contrary, “Public spending is always a substitute for private spending.”[2] Although ordinary taxpayers have no power or authority to spend their money directly on armies, interstate highways, public schools or police forces, their private money is allocated to do exactly that. Look at where the money comes from. “This is the other side of the coin.”[3] When you are taxed to keep your house, you no longer have that money “at your disposal.”[4] Thus, your savings and wages, dividends, interest earnings or pension income is reallocated from you to a governmental spending unit. This isn’t a gain for you, but a reallocation. If you don’t value the objects of the public spending as much as what you lose in taxes, then you will feel a net loss of your subjective well-being and a constraining weight upon your future outlook.

You will suffer from high Spending Pressure. High governmental Spending Pressure.

[1] See, Stevenson, The Search for the Fountain of Prosperity,” at 3.

[2] Frederic Bastiat, What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850) Sec. 4 “Theaters and Fine Arts”.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

Your home or commercial property may go up or down in value. The money needed by units of government, however, does not decrease just because your property goes down in value, which is why your taxes can go up even if the value of your property goes down. Because they keep right on spending.

Your consequent Spending Pressure increases the tax claims against your property. Spending, in turn, is funded not only by the amount taxed from you right now, but also by the amount that the spenders have borrowed from someone else, adding to the amount that must be spent later to repay the debt. Payment will be made from taxes on you.

We must remember all of that borrowing, since the debts owed to government creditors become assets held by those lenders. In this sense, the promise made to a lender is an assurance of spending unseen. Current taxes are “only…immediate; since taxing “manifests itself simultaneously with its cause---it is seen.” Whereas debts “unfold in succession—they are not seen”[1] until they arrive in the form of future taxes.

Consider all of the Spending Pressure you feel as a simplified proof of your existence: “I am taxed, therefore I am.” Spending Pressure shows how strenuously you need to exist to pay your way through life in a jurisdiction more heavily pressurized against you.

Spending is the key to it all.

[1] Fredric Bastiat, What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850) from Introduction.

Alchemists of old insisted that moonbeams turned base metals into silver, in a process where “magic and chance…take the place of natural law in the universe.”[1] Today, government spenders turn your house into cash by shining a tax levy onto it.

When a unit of government, let’s say a local park district, adopts a budget requiring an increased levy of taxes to be divided up by your township assessor among all of the “equalized assessed value’ of the property located within that district, it seems to those government employees that “millions of [dollars] descend miraculously on a moonbeam into the[ir] coffers.”[2] Users of nice new expanded park district facilities tend to adopt the same “moonbeam” outlook themselves, even while appealing their tax bill based on comparisons of their home’s square footage with the house next door. Because even those who enjoy government spending don’t want to pay the cost of it.

Even the public employees who glean things like lifetime teacher, fire or police pensions know this. Look what they typically do: Work just long enough to qualify for the maximum pension funded by your high taxes, and then move to a “cheaper” State to retire. Their destination State has lower taxes where their pension income goes further and lasts longer. Because unlike the higher pressure State that funds their pension, the low pressure State to which they move has lower taxes. Because the lower pressure state spends less per capita in the first place.

That’s why everyone says: “I can buy twice as big of a house in Tennessee but only have 20% of my current tax bill here.”

So if you find that you are living in a higher pressure State engaged in things like spending on pension creation for public employees who are going to leave anyway, consider the relative benefit of moving yourself to a lower spending pressure place during your peak earning years.

Especially if you now see that those spending Moonbeams are just destroying your silver.

[1] Marden, Orison Swett. The Secret of Achievement (Timeless Wisdom Collection Book 6) (p. 15). Business and Leadership Publishing. Kindle Edition.

[2] I Frederic Bastiat, What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850), Sec. 4 “Theaters and Fine Arts”.

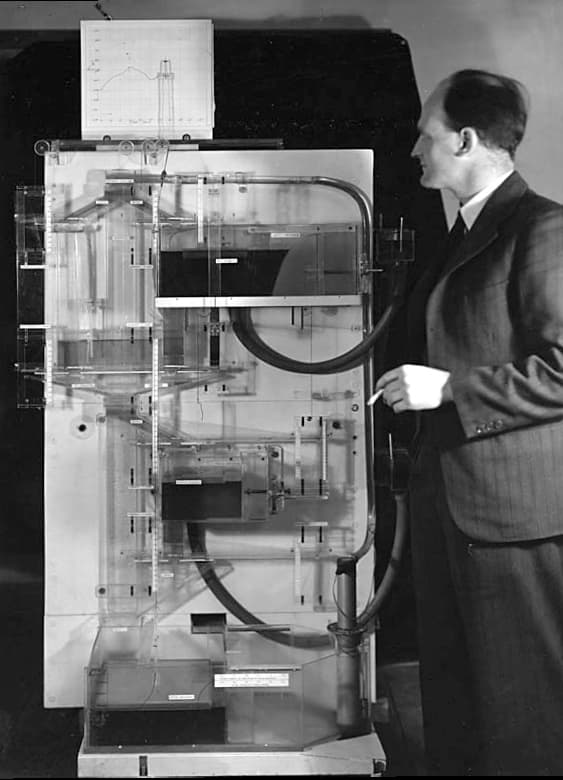

Models of the economy include simple drawings, complex math equations, and even analogue computers using fluids and pipes to mimic the circulation of income, taxes, savings and investment flows.

Here is the famous Monetary National Income Analogue Computer (MONIAC) invented by Bill Phillips in 1949, which used a water pump to actually pressurize colored fluids from one tank to another “to represent taxation.”[1]

Although the MONIAC had its fans, the “Phillips Curve” it was used to derive fell into disrepute by the 1970s. Our Spending Pressure model is not so ambitious, but still draws on the “fluid logic” that taxes pump out dollars from the private economy, and that differential pressure is exerted on parcels of real estate depending on the location of that real estate in relation to the differential behaviors of disparate taxing jurisdictions.

As a result, Spending Pressure can not only be calculated, but geolocated. We don’t need to create a model of the whole economy. We can simply map the Spending Pressure in your own personal economy. Right where you live, or may want to live, in the economic units of your town, county, state and country. There’s a tradeoff between what you keep and what the government takes. Different zones have different pressures, based on the volume of taxes different units of government trade for your personal assets.

[1] Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=MONIAC&oldid=1100226655

“When a government official spends on his own behalf one hundred [dollars] more, this implies that a taxpayer spends on his own behalf one hundred [dollars] the less. But the spending of the government official is seen, because it is done; while that of the taxpayer is not seen, because—alas!—he is prevented from doing it. You compare the nation to a parched piece of land and the tax to a life-giving rain. So be it. But you should ask yourself where this rain comes from, and whether it is not precisely the tax that draws the moisture from the soil and dries it up. You should ask yourself further whether the soil receives more of this precious water from the rain than it loses by the evaporation.”[1]

Spending Pressure measures that.

Complexity Theory and various Alternative Economic Models use metaphors to enhance understanding of economics.[2] A challenge is to present aggregate levels of something like all government spending, “as when gas pressure is considered an emergent phenomenon nonetheless completely reducible to individual gas molecules.”[3]

That’s Spending Pressure. We reduce the aggregate pressure of all of the spending to individual units of government all pressurizing your specific address. You can then investigate the specific identity of the spenders manning each unit of government, and the budgets they produce that add up to your Spending Pressure. We give you the initial comparative tool to perform your own differential diagnosis. As the academic writers describe it:

emergence [of Spending Pressure] is assumed to exist at aggregate or upper-level states of systems even though it is conceived in reductionist terms and thus fully retraceable to individual, lower level components.[4]

Our input data is all certified as accurate by the U.S. Census Bureau. Unlike some economists, we don’t make up exemplar data, or postulate states of perfection to make our numbers work. They are the government’s own numbers. We just map them to your address with our programming.

All of which shows using the government’s own data that when government spends more, you have less. The less you have, the more you suffer from Spending Pressure.

[1] Fredric Bastiat, What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850) Sec. 3 “Taxes”

[2] See, for example, Bier and Schinkel, Building Better Ecological Machines: Complexity Theory and Alternative Economic Models, Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 2 (2016), 266-293.

[3] Supra, fn. 2. At 274.

[4] Id. The authors go on to point out that such a model is “founded on …principles of fixed, integrated parts that add up to a whole and have a set of fixed mechanistic outputs for a set of determined mechanistic inputs.” (284).

We use only U.S. Gov’t Census Data. Which means it must be true. “For heaven’s sake, gentlemen, at least respect arithmetic.”[1] We tend to think that additional spending by a unit of government adds something that was not there before, when really it just reallocates it. We do the arithmetic and let you compare it between government zones by property addresses anywhere in the United States. “What a lot of trouble to prove in political economy that two and two make four; and if you succeed in doing so, people cry, ‘It is so clear that it is boring.’ Then they vote as if you had never proved anything at all.”[2]

The organizing metaphor of Spending Pressure drawn from the medical world of Blood Pressure is “an important shift” in what economists call “the organizing metaphors of… economic models.”[3]

The implication of your ability to calculate your own residential spending pressure, and to compare it to an alternative address opens to you a previously “complicated and possibly unquantifiable aspect” of your society and personal economy.[4]

So check it out. Run the numbers for your address. Math doesn’t lie.

[1] Frederic Bastiat, What is Seen and What is Not Seen, Sec. 3 “Taxes” (1850).

[2] Id.

[3] Bier and Schinkel, Building Better Ecological Machines: Complexity Theory and Alternative Economic Models, Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 2 (2016), 266-293, at 285.

[4] Id.